This story exists to revisit a little-remembered chapter in palm history—one that offers important lessons about discovery, demand, and conservation. While the Foxtail Palm is now a familiar sight around the world, its path from obscurity to fame is far more complex than most people realize.

The remote Melville Range in far-north Queensland—home to the only known wild population of the Foxtail Palm and the setting of one of palm history’s most unusual conservation controversies.

A palm you see everywhere—born from secrecy

Today, the Foxtail Palm feels ubiquitous. It lines boulevards, anchors resort landscapes, and appears in gardens across warm climates worldwide. Yet few people realize that Wodyetia bifurcata did not follow the usual path from scientific discovery to cultivation. Instead, it became popular first—and understood later.¹

The Foxtail Palm became globally popular before botanists could even say where it came from.

That reversal—fame before formal recognition—set the stage for a chain of events now remembered as the Cape Melville incident, a story that blends botany, mystery, profit, and conservation risk.

The Foxtail Palm before anyone knew its name

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, palm growers in Australia began encountering a remarkable new palm. It grew quickly, developed a smooth, self-cleaning trunk, and produced a dense, plume-like crown unlike anything else in cultivation. Demand followed immediately.

What didn’t follow was certainty.

Seeds appeared quietly in horticultural circulation, often mislabeled or vaguely described, and speculation about the palm’s origin flourished. New Guinea, Indonesia, and even hybrid origin theories were proposed—but none were correct.²

Cape Melville: a locked vault of palms

The breakthrough came in one of Australia’s most forbidding landscapes: Cape Melville, a rugged massif on Queensland’s Cape York Peninsula. Dominated by massive granite boulder fields and dense rainforest, the region had remained largely unexplored by botanists for decades.³

When researchers finally accessed the area, the discovery was startling.

An internationally desirable palm was clinging to survival on a single mountainside.

The Foxtail Palm existed naturally in one extremely small, isolated population, protected for millennia by geography rather than law. In 1983, the species was formally described and placed into its own genus—Wodyetia—a rare acknowledgment of its distinctiveness.⁴

When rarity meets demand: the seed rush begins

By the time science caught up, the market was already racing ahead.

The Foxtail Palm’s beauty and scarcity translated into unusually high early prices for seed and seedlings—figures repeatedly described in contemporary and later accounts as exceptional for a palm species at the time.⁵ In a pre-internet world, exclusivity drove value, and value drove behavior.

Illegal seed collection followed.

Collectors targeted Cape Melville repeatedly, harvesting seed from a population that had no natural resilience to exploitation.

Admiration quickly turned into pressure—and pressure became exploitation.

The Cape Melville incident explained

The term “Cape Melville incident” refers to events that came to a head in November 1993, when park rangers raised alarms about suspected illegal Foxtail Palm seed collection within protected land. What began as a conservation enforcement issue quickly escalated.⁶

Investigations followed, media attention intensified, and the issue entered the political arena. Allegations surfaced, vehicles were seized, and questions were raised about influence and interference. For a brief moment, a palm species—previously unknown to most of the public—became the focus of national scrutiny.

So… Were There Villains?

This is where many retellings drift into rumor.

There is no single, universally documented “villain” in the Cape Melville incident—no infamous collector permanently etched into botanical history, no definitive courtroom resolution. What is clear is that illegal seed collection occurred and that profit incentives were real.⁷

The most damaging force wasn’t one person—it was the gap between demand and knowledge.

Some individuals undoubtedly placed short-term gain ahead of long-term survival. Yet the public record is far clearer about the existence of a black-market trade than about who benefited most from it. Names occasionally appear in secondary accounts, but verified outcomes—documented fortunes, convictions, or formal botanical sanctions—remain elusive.

In many ways, that ambiguity is the lesson.

The great irony: cultivation saved the species

Here’s the twist most people miss.

The same global demand that endangered the Foxtail Palm in the wild ultimately ensured its future. As legally cultivated palms matured and seed production expanded, prices fell. The incentive for illegal collection diminished, and pressure on the wild population eased.⁸

The Foxtail Palm survived because cultivation finally outran exploitation.

Today, the Foxtail Palm is one of the most widely planted ornamental palms on Earth—yet its wild ancestors still persist in just one extraordinary place.

Why this story still matters

The Cape Melville incident feels strikingly modern. It mirrors today’s viral plant trends, rare-species hype, and ethical debates around collecting and conservation. The difference is that this unfolded decades before social media accelerated everything.

The story reminds us that:

- popularity can endanger species

- conservation often lags behind demand

- transparency matters—especially early

Sometimes, the plants we think we know best have the most complicated pasts.

Editor’s Note from Project Palm

At Project Palm, accuracy matters.

Some versions of the Cape Melville story repeat speculation as fact. In researching this article, we found strong evidence of illegal seed harvesting and legitimate conservation concern—but no definitive, responsibly sourced proof identifying specific individuals who amassed fortunes or were formally condemned by the botanical community.

Rather than repeating rumor, we’ve chosen to present what is known, acknowledge what remains unclear, and focus on the broader lesson: how fragile conservation can be when demand outpaces understanding.

Sometimes, the most important stories aren’t about villains—but about vulnerabilities.

Postlogue: When One Palm Became a Legend—and Another Did Not

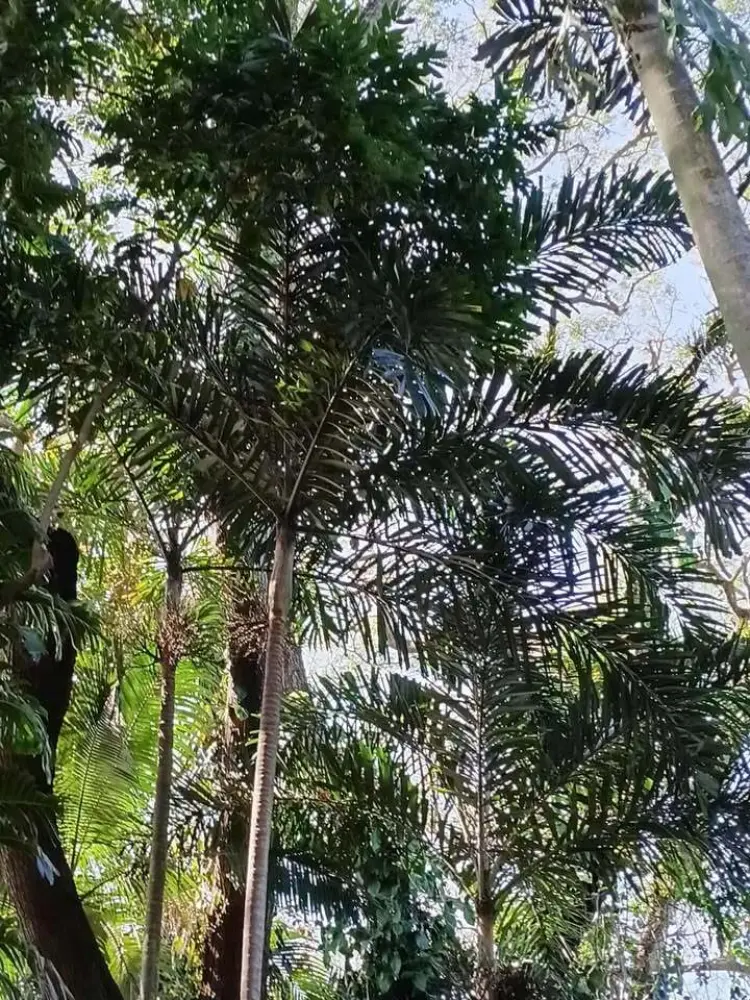

The impact of the Cape Melville incident becomes even clearer when viewed in regional context. In the rainforests of far-north Queensland—just a few hundred kilometers south of Cape Melville—another striking palm evolved under similar ecological conditions, yet followed a very different path into cultivation: Normanbya normanbyi. Comparing these two species reveals how controversy and timing helped propel one palm into global prominence, while the other remained largely regional despite its beauty.

The Cape Melville incident did more than expose a conservation vulnerability—it helped define the global future of Wodyetia bifurcata.

Scarcity, secrecy, and controversy created an aura of urgency around the Foxtail Palm at precisely the moment when the international palm trade was expanding. Long before most growers fully understood its ecology or origin, the species had already acquired a reputation: rare, beautiful, and briefly unobtainable. That narrative—combined with rapid growth, strong ornamental appeal, and broad adaptability in cultivation—transformed the Foxtail Palm from an obscure rainforest species into a global landscape staple.

Normanbya normanbyi, by contrast, followed a quieter and more traditional path. Native to the rainforests near Cairns, it was known, described, and introduced to cultivation without secrecy or scandal. Its rise was measured rather than meteoric, its origins never mythologized. As a result, it never benefited from the surge of international demand that propelled the Foxtail Palm into widespread production.

In North America, this divergence remains evident. The Foxtail Palm’s tolerance of brief cold, moderate drought resistance once established, and immediate visual impact made it an ideal candidate for large-scale nursery production. Normanbya, while equally elegant, proved slower to establish, more dependent on consistent moisture and humidity, and less forgiving outside of strictly tropical conditions.

Together, these two Queensland palms illustrate a subtle but powerful truth: popularity in cultivation is shaped as much by narrative and timing as by botany. One palm survived a brush with exploitation and emerged ubiquitous. The other avoided scandal—and remained regional. Neither outcome was inevitable, but viewed side by side, they reveal how discovery, demand, and horticultural practicality quietly shape a species’ fate long after it leaves the rainforest.

Notes & Sources

1. Early cultivation and trade of Foxtail Palm seed prior to formal scientific description is widely noted in palm society literature and historical horticultural accounts.

2. Misattributed origins and early speculation are discussed in secondary palm literature and early nursery trade commentary.

3. Geographic isolation and ecological characteristics of Cape Melville are documented in Queensland botanical surveys and conservation summaries.

4. Wodyetia bifurcata was formally described in 1983 in the journal Principes, establishing a new monotypic genus based on morphology and distribution.

5. Historical accounts frequently cite unusually high early seed prices, reflecting scarcity and collector demand; precise figures vary by source.

6. Queensland Parliamentary Records (1994) and Australian media reporting reference investigations and controversy surrounding Foxtail Palm seed collection in Cape Melville during the early 1990s.

7. Documentation supports the existence of illegal harvesting and black-market incentives, though definitive individual profit outcomes are inconsistently recorded.

8. Expansion of legal cultivation reducing pressure on wild populations aligns with broader conservation economics observed in formerly rare ornamental plants.